They called them the avocado rooms.

It was there, in those mild-green offices in the basement of the Forrest Building, that a group of determined Dal students assembled in the early 1970s with change on their minds.

The Ecology Action Centre (EAC), as the collective labelled itself, produced in-depth reports, carried out awareness campaigns and organized on-the-ground initiatives, all from the cozy confines of their humble campus quarters. And it was there that the outfit stayed for the better part of a decade and a half, rent free, before spreading its wings to seek a larger nest to house a growing contingent of staff and volunteers.

Dalās role as a benefactor to EAC during those early years created a strong bond between the two institutions. Itās a partnership that has served both well over the decades and continues to today as the latter celebrates its 50th anniversary starting this week on Earth Day (April 22).

But in those chilly days of December 1971, as the group moved its operations from a makeshift headquarters in a co-op house near Dal to the university's Forrest Building, there was a more immediate consideration at hand.

āWe decided to paint the rooms avocado. It was one of those colour-of-the-year choices at the time,ā recalls Brian Gifford (BAā71), one of EACās founding members who had just graduated from Dal earlier that year.

The little centre that could

The group even touted its āavocado roomsā in a letter to supporters at the time informing them EAC had been offered the offices thanks in large part to the advocacy of Sociology professor Don Grady.

The new space was a stroke of good fortune after a year of ups and downs for the fledgling group.

āEAC had some years when it really struggled. That first year, we were volunteers for a while and that has happened another time or two during its history,ā says Gifford, shown right in 1972.

Gifford and another member had to bootstrap the operation on their own that year for a few months after their initial funding from a federal student grant ran out. Virtually overnight, the group shrank from a staff of five people to two.

Gaining office space helped rebuild their resolve, though, and by the time the paint had dried in the rooms theyād also managed to line up some new grant money.

The birth of a movement

Managing grant cycles can be a challenging endeavour for many non-profits, particularly new ones still trying to build their networks and influence. But EACās ability to weather these difficult periods, particularly early on, had a lot to do with the underlying passion and commitment of its staff and members.

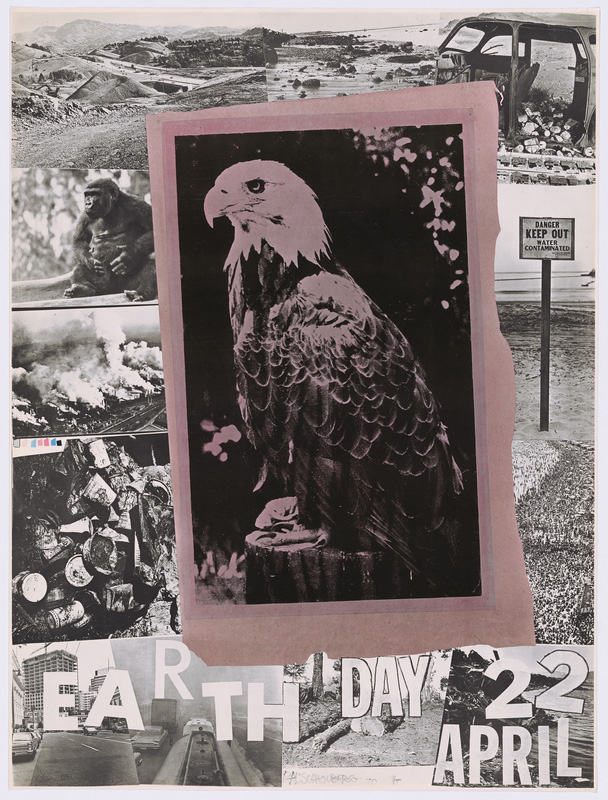

The late 1960s and early 1970s were heady times for social movements. Awareness about environmental degradation was growing as the impacts of widespread pesticide use and fossil fuels were examined more closely. Rachel Carsonās book Silent Spring, first released in 1962, had become a revered tome by many environmentalists who identified with its call for humans to serve as responsible stewards of Earth and its resources. And then in April of 1970, millions of Americans turned up in streets, parks and auditoriums across the country with air and water pollution on their minds to mark the first-ever Earth Day ā now considered one of the largest secular days of observance in the world.

The late 1960s and early 1970s were heady times for social movements. Awareness about environmental degradation was growing as the impacts of widespread pesticide use and fossil fuels were examined more closely. Rachel Carsonās book Silent Spring, first released in 1962, had become a revered tome by many environmentalists who identified with its call for humans to serve as responsible stewards of Earth and its resources. And then in April of 1970, millions of Americans turned up in streets, parks and auditoriums across the country with air and water pollution on their minds to mark the first-ever Earth Day ā now considered one of the largest secular days of observance in the world.

Above, poster for the inaugural Earth Day by artist Robert Rauschenberg. (National Archives, Records of the U.S. Information Agency)

It was in this climate that a group of Dal students, including Gifford, came up with the idea for Living Ecology, a student-led course that would allow them to pursue environmental initiatives for credit.

At the time, Dal offered an experimental course program that allowed students to come up with ideas for courses and find sponsors (usually faculty members) to help run them. It was a way for students to better customize courses to their interests.

Another stipulation of experimental courses was that they offer a tangible way to assess student learning.

āThe expectation was that for your mark you would create some kind of an action,ā says Gifford, āso a few of us decided to start this organization to complete the course.ā

Taking action

If big ideas were the fuel for EACās fire, it was the little details that really paid off when it came to successful campaigns and advocacy.

One of the groupās earliest initiatives involved building support for recycling in Halifax. Still a somewhat fringe idea at the time, and one that may have seemed complex in an era before widespread solid-waste management, EAC set out to show small changes in day-to-day behavior could have an impact. It set up a paper-recycling depot that processed a ton of paper every Saturday between 1972 and 1975.

By the end of the decade, the group had organized a major paper-recycling project in Fairview and Spryfield that got close to 20 per cent participation from households. That project was cancelled shortly thereafter, though, but for a positive reason: a private company had stepped up to offer a city-wide collection service. In time, recycling and solid-waste reduction became a provincial priority as well and Nova Scotia was eventually heralded as a leader in the sector in North America.

EAC's paper-recylcing depot.

Devising straightforward, evidence-based approaches to tackling issues has remained at the heart of the organizationās approach. Only now, it does so across a much broader range of issues, including food, biodiversity, energy, climate and transportation, to name a few. Ā

āOne of the things thatās interesting in these stories is they are not fights that you win in a month or a year. They are ones you win over decades and that you follow for decades,ā says Maggy Burns (BA'95, BSc'01), EACās interim executive director and a Dal alum.

Take transportation, for example, a topic first placed on the groupās agenda as far back as the 1970s and one that would ultimately come to greatly benefit many »ĘÉ«Ö±²„ students. At the time, EAC had produced a book called A Time for Transit and had organized a car-pool program that would bring people into the downtown core to relieve congestion and reduce the number of vehicles on the road. Decades later, in the early 2000s, with the help of an enterprising young staff member who had recently graduated from Dal, EAC put together an advocacy campaign to institute a student-bus pass program at universities in Halifax. Stephanie Sodero (MESā01), the staffer, had done her masterās research project on the topic and the results of her interviews with Dal students, faculty and staff informed the campaign.

āIt was a cool partnership between students, the transit authority and EAC where the result is cheaper bus passes for students, more consistent parking demand on campus, easier access for students, clearer demand for Metro Transit and fewer car trips,ā says Burns of the program, commonly known as UPass.

Ā āWeād been pushing for this for quite a while.ā

Intertwined impact

This is one of hundreds of examples of the ways Dal and its alumni, staff and students work with EAC to enact change, says Burns. Many are part of its 4500-5000-strong membership, several have been or are staff members or among the more than 1,000 people on the groupās volunteer list.

āEAC is brilliant at building partnerships, connections, coalitions. If we did a full inventory of all of that and looked at everyone involved, thereās no doubt weād find a lot of Dal involvement. Thereās a million and one volunteer stories,ā says Burns.

And these connections often turn into valuable relationships over the years, as has been the case with Rochelle Owen, Dalās director of sustainability, shown left. Owen did a volunteer placement with EAC in 1987 during her second year of undergraduate studies. Later, she served on the Board and has been a donor for a long time.

And these connections often turn into valuable relationships over the years, as has been the case with Rochelle Owen, Dalās director of sustainability, shown left. Owen did a volunteer placement with EAC in 1987 during her second year of undergraduate studies. Later, she served on the Board and has been a donor for a long time.

"I believe in the importance of giving back to the community and volunteering," says Owen. "EAC works on a breadth of provincial-wide programs, from community and school-based action projects to policy development, advocacy, and research. The impacts of those initiatives can be seen in the creation of new organizations, regulation, new programs, and more."

When EAC was renovating its headquarters on Fern Lane a few years ago, Owen offered up salvage materials from a number of demolition and renovation projects happening at Dal at the time. EAC's fire doors are from a residence that was taken down and some slabs of wood from the Killam Memorial Library now serve as boardroom tables.

Just as Dal had offered up its physical space to EAC in the early years, here it was once again offering physical support to the organization, only this time by diverting its waste from the landfill to support an affordable renovation.

āThe physical connection between Dal and EAC is really neat,ā says Burns. āTo see some of that material flow back into the building was really powerful.ā

Fern Lane renovation before-and-after.

A return

In 2010, Gifford was preparing to enter retirement after a career working in the non-profit sector, mainly for affordable housing organizations. With some extra time on his hands, he knocked on EACās door.

Although he had worked on the odd project and report for the group following his departure as coordinator in 1975, heād lost touch with the group over the 13 years when he was working out of the province. During a trip back to Nova Scotia one summer, he attended a reunion of earlier staff at EAC. There, he realized how far EAC had come in those years he'd been away was away. He signed up as a member and volunteer.

āIt was really marvelous. It was a very different place. It had really come into its own by that period and had a lot more staff. They were involved in a lot more activities and issues and doing a really super job. You heard them on the radio a lot. You could see from the activity they were doing that there was a lot of really good work going on,ā he says.

Still, it didnāt take long for him to get reacquainted with EAC and for that initial enthusiasm fostered in the avocado rooms to return.

āIt was pretty exciting to know that it was still going and to be involved again.ā