Sciographies is a radio show and podcast about the people who make science happen, brought to you by the Faculty of Science and campus-community radio station CKDU. This article is the fifth in an eight-week series that features excerpts from each new Sciographies episode this fall. You can find Sciographies on Apple and Android podcast apps, by tuning in to CKDU 88.1 FM in Halifax at 4 PM Thursdays (until October 31), or by visitingÃ˝dal.ca/sciographies or .

Sciographies is a radio show and podcast about the people who make science happen, brought to you by the Faculty of Science and campus-community radio station CKDU. This article is the fifth in an eight-week series that features excerpts from each new Sciographies episode this fall. You can find Sciographies on Apple and Android podcast apps, by tuning in to CKDU 88.1 FM in Halifax at 4 PM Thursdays (until October 31), or by visitingÃ˝dal.ca/sciographies or .

Ã˝

Eric Oliver recognized his knack for math and physics in the first year of university. By the time senior year rolled around he was already exploring quantum computing problems (and hosting a campus radio show). But after pursing a Master’s in the same discipline, he missed classical physics. Dr. Oliver decided to pursue a PhD in physical oceanography here at Dal (PhD’11) because within that field, he could apply his interest in classical physics to planet-sized models: Earth’s ocean and atmosphere.

Today, Dr. Oliver has returned to his alma mater as an assistant professor in the Department of Oceanography. His research covers ocean and climate modelling. Some of his latest work explores extreme sea surface temperature variability — in other words, marine heatwaves. They’re just like those experienced on dry land, but instead their impacts can wreak havoc on marine ecosystems already living in warmer than usual conditions because of climate change.

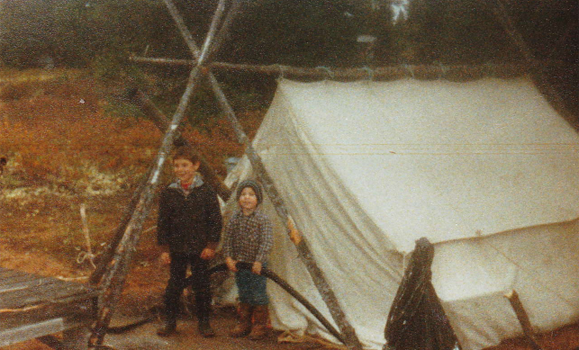

Dr. Oliver and his brother standing outside of what they call a “Labrador tent.”

Hailing from Labrador, Dr. Oliver is of Inuit-descent with roots in Rigolet, Nunastiavut. He always wanted to give back to his home community and now he can through research. has recently secured funding to develop ocean research projects with and for Inuit communities on the North coast of Labrador and that work is ramping up now.

In this episode of Sciographies, host and oceanography professor David Barclay speaks with Dr. Oliver about the increasing occurrence — and intensity — of marine heatwaves in the ocean. Dr. Oliver also shares his hope for a future in which traditional ways of knowing are combined with scientific data to conduct research with meaningful impact for Indigenous communities and partners. Here are a few excerpts (edited for length and format).

Dr. Oliver, on his former hobby…

Barclay: Tell me about the last time you were here at CKDU.

Oliver: I was here something like 10 years ago because I did my PhD here at Dal. I wanted to have a radio program; I had one when I was in my undergrad [at Acadia University] … It was on a digital station so I could see how many people were connected to my 70’s prog-rock program called Open Your Eyes.

Barclay: And what was the average listener count?

Oliver: Between three and six? Something like that. I probably knew them. [laughs]

… On the importance of studying marine heatwaves

Barclay: Are the heatwaves impacting where marine life is going?

Oliver: Well, 10 years ago on the coast of western Australia, kelp forests were supporting a particular ecosystem. And then in 2011, this massive marine heatwave came along and stressed everything out. The kelps system collapsed and was replaced by sea grass—and that was a temperature response. Then the [heatwave] subsided and temperatures went back to normal. But the system stayed changed. So, I think of it like a ratcheting effect. You’ve got this gentle pressure from climate change but on top of that are these impulse marine heatwaves that kind of ratchet, step-by-step, the ecosystem impacts.

Dr. Oliver conducting fieldwork in Nain, Nunatsiavut.

… On reconciliation within a scientific research context

Barclay: Do you think that combining the two ways of knowing (i.e. scientific data and traditional knowledge) is effective as a form of reconciliation?

Oliver: It’s all still very new to me, but I think bringing it up and being able to have a conversation is a big part of it. Maybe there are cases where we talk about the two kinds of knowledge for a particular research question and it doesn’t work. I guess you could interpret that as reconciliation, right? Because we’re having an open conversation about this rather than [approaching it with] a biased view… I would like to see traditional knowledge information not treated as somehow less than.