Sciographies is a radio show and podcast about the people who make science happen, brought to you by the Faculty of Science and campus-community radio station CKDU. This article is the fourth in an eight-week series that features excerpts from each new Sciographies episode this fall. You can find Sciographies on Apple and Android podcast apps, by tuning in to CKDU 88.1 FM in Halifax at 4 PM Thursdays (until October 31), or by visiting dal.ca/sciographies or .

Sciographies is a radio show and podcast about the people who make science happen, brought to you by the Faculty of Science and campus-community radio station CKDU. This article is the fourth in an eight-week series that features excerpts from each new Sciographies episode this fall. You can find Sciographies on Apple and Android podcast apps, by tuning in to CKDU 88.1 FM in Halifax at 4 PM Thursdays (until October 31), or by visiting dal.ca/sciographies or .

It’s not uncommon for university students to explore new subjects and career paths after living, working, or studying abroad. Just ask Megan Bailey, an assistant professor in »ĆÉ«Ö±˛Ąâ€™s Marine Affairs program. The seeds for her career as a fisheries economist were first planted when she decided to follow her curiosity while working as a field assistant in Suriname, South America.

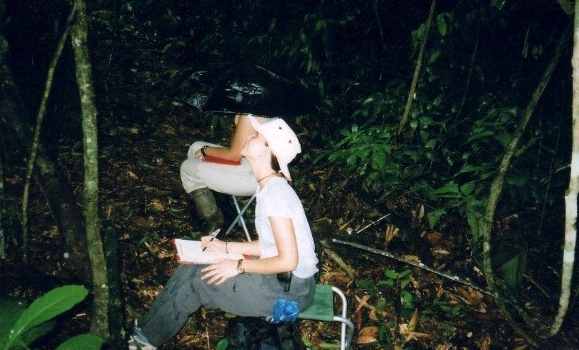

Dr. Bailey grew up in London, Ontario with a love of animals that led to a zoology degree. She then spent a year studying monkey behavior in the Suriname jungle, hoping to one day become a primatologist. While there, though, she found her mind was occupied with questions about the jungle’s natural resources and how local communities were using them. When Dr. Bailey returned to Canada she course-corrected her career path and pursued an interdisciplinary Master’s and PhD in fisheries economics instead.

Now Dr. Bailey is a Canada Research Chair in Integrated Ocean and Coastal Governance. Her research informs public and private policies around seafood production and consumption all over the world. Dr. Bailey’s motivations are guided by the belief that ocean resources can be governed in ways that consider both ecological resilience and the social-wellbeing of communities that rely heavily on local fisheries.

In this week’s episode of Sciographies, host and Dal oceanographer David Barclay interviews Dr. Bailey to chat about her artistic hobbies, changing focus, and what it’s like to work at the intersection of ecological science and social science. Here are a few excerpts from the episode (edited for length and format).

Dr. Bailey records observations of a brown capuchin monkey troop in Raleighvallen, Suriname.

Dr. Bailey, on how her field experience in Suriname changed her perspective…

Barclay: You spent a year in the jungle?

Bailey: Yes, in a protected area called Raleighvallen on the Coppename River. We studied a troop of brown capuchin monkeys. Every day we’d find them and write down what they were doing. There were a couple reasons why that wasn’t really my thing. One was related to the subjective nature of those observations… But also, we were in this protected forest. I came down [from London, Ontario] being like we need to save the rainforest and understand these monkeys. I got there, and there were people that lived near our field station who had to cut down trees for their home, fish in the Coppename River for their food. They ate monkeys; our monkeys! It was this total awakening. Like, wow, who do we save the rainforest for? Or, who has a right to use resources? Or, what is the human dimension of resource use?

On geopolitical power dynamics in seafood production and procurement…

Bailey: There’s this geopolitical situation around seafood where a lot of what we import in the developed world comes from the developing world. So as the U.S., Canada, the EU, and Japan put conditions on how fish should be caught and how seafood should be procured, what we’re really doing is operating in a dynamic of power by saying how other people should manage their fish, how other people should live their lives, who should or shouldn’t get a job.

Barclay: What kind of conditions are we talking about?

Bailey: For example, if we look for eco-labelled seafood here in the supermarket, you find labels indicating that the seafood was sustainably caught. That means it’s met a set of standards around ecological sustainability. That’s fine, there’s nothing wrong with that. Except that it discriminates against a fishery or country where there isn’t a lot of government oversight, or where fishing is really important because there’s high unemployment rates… if [fishing data] isn’t collected, you’ll never get a label that says [the seafood came from] a sustainable amount of catch, right? And if those data aren’t collected or made public, then those fisheries get dropped out of the global market, basically.

On the importance of fieldwork in social science research…

Barclay: How do you balance your research findings with your experiential findings?

Barclay: How do you balance your research findings with your experiential findings?

Bailey: I did fieldwork during my master’s in Indonesia and my PhD was mostly desk-based. Then during my postdoc, I had a lot of field time. I look back on my PhD and think, oh, I would have written that so differently had I had spent more time in the field… For us in social sciences, we often try to take what's called a participatory action-based research approach, where we're constantly in the field and in communication with partners—everything's collaborative. And it’s all iterative… when we think about the [economic] models that tell us countries should work together, maybe that happens in a moment in time, but there's so much transition in governments that those political realities have a huge influence on what we can actually achieve in conservation and equity outcomes. If you don't follow the political process in those countries, you have no idea. You have expectations about how a country should operate, but those aren't your expectations to make.

Photo above: Dr. Bailey, after catching her first Arctic char while working up in Nain, Nunatsiavut, learn more about the importance of the char fishery to the community.

Dr. Bailey and Dr. Barclay recording this episode of Sciographies in CKDU’s studio. Â