An interview with Daniel Salas-González, a Killam scholar and Social Anthropology PhD student studying the political economy of the Cuban transnational community.

Q: Why did you choose »ĆÉ«Ö±˛Ą?

I first came to »ĆÉ«Ö±˛Ą for five months in 2012 on an Emerging Leaders of the Americas Program scholarship, and I loved the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology.

»ĆÉ«Ö±˛Ą has one of the longest standing and most important exchange programs with Cuba. So I had met some people who had been in contact with »ĆÉ«Ö±˛Ą, and Canada was my first choice in terms of going abroad. I wanted to explore the opportunities for professional improvement.

Q: Would you have come to »ĆÉ«Ö±˛Ą for your PhD if you had not first spent time here as a visiting researcher?

I had the chance to glimpse what I would be experiencing. Probably yes, I would have applied for the PhD and done all the rest, but it is four-to-six years of my life. And I came with my wife so I had to convince not only myself but also another person.

Q: How have you found the move to Halifax?

For me the transition has been very smooth. As smooth as it can be as I had been working, and the rhythms of working are different from those of a full-time student. There was that first shock of getting into the discipline, of reading and writing against the clock. Get to classes on time, stay up all night writing your response, all of that. But after a month I was loving it so much. I was feeling that I was doing what I love the most.

My wife and I love the city, we love the people. We haven't really had bad experiences at all. It is a different culture and language. The better you can speak the better you can interact and get along.

Q: Are you liking Canada?

Canada is a very pleasant place to live. It is not very challenging, people don't expect you to change to fit, and they are very helpful, supportive.

Coming from a different culture you see things that Canadians don't see as you are coming from a different perspective. I noticed the distance in interactions in the sense of physical space, of not touching, for instance. When I was getting used to it I felt that it was kind of a cold environment, but this is not right, people are not so much cold as respectful of each persons’ space and body and the distance between individuals.

Q: And winter?

We did our best to survived it, like the rest. Last winter was, according to most people, the worst ever. But when I came here three years ago people were saying the same thing! So it looks like there might be a pattern. Being my second Canadian winter, it did not lack a certain charm of novelty, at least for the first couple months, I have to say.

Q: Have you always been an academic?

I was a Journalism major in Cuba, teaching in the Faculty of Communication at the University of Havana. What interested me more than anything else was telling peoples’ stories. I wanted to be a novelist when I was younger and that is why I went to journalism school.

Along the way I found myself drawn to pursue a career in an academic area rather than as a reporter. Not to mention that journalism in Cuba is not the best profession to practice. I was lucky enough to stay in the University of Havana in different roles and eventually to be a professor of journalism. I taught from 2007-2014, with minor interruptions, and at the same time I was working at several journals.

Q: What does your experience as a journalist in Cuba bring to your research?

I am concerned with intellectuals and the public sphere, and with the democratic potential that the formers could bring to the latter. The actual way that journalism was carried out in Cuba, by the most important media, has been very closely state controlled. The interesting things were not taking place there. So I was trying to bridge these two areas, and in doing so trying to find out more about society, culture and how they are both shaped by power relations.

Q: What connections have you found between your work in the media and in Social Anthropology?

Journalism andsocial anthropology are not the same, but there is a shared substratum of interpersonal contact, of putting the effort in to find the person and cover the story and construct meaning. To understand what is going through their senses, their minds, and their lives. There are important common features, and I hope that eventually I can put into practice what I learned in journalism: to make things relevant, comprehensible, interesting. To share the stories that people have to tell.

Q: How has your project changed and developed?

I began with a project on the public sphere and intellectuals, which I had been working on for some years. After actually putting a good amount of work into that project, making interviews and so forth, I decided to change topic.

Here I have had a chance to appreciate the type of research that anthropologists do on subjects like the economy and money. Being in touch with incredible professors, in particular my supervisor Professor Lindsay Dubois, also made me rethink my proposal. So I decided to go back one step and tackle the economy. That also entails a shift in emphasis from the most visible players in society to the less visible ones. So I plan instead to look at the economic day to day reshaping of the society, at what people are making in their lives not only in my country but across the transnational social field that reaches out to Cuban diasporas.

Q: What can you tell me about your research?

I am studying issues related to the political economy of the Cuban transnational community in the recent past. This is a period during which the country as a whole is increasingly becoming entangled in what we normally call globalization, although with many limitations imposed by the hostility with the U.S. and the reluctance of the Cuban government to lose its grip on society. My research points to understand how migrants and their families and acquaintances staying in Cuba constitute networks that permit the circulation of money, persons, things, services, ideas, all which we may regard as "values," in a general sense.

I want to explore how these exchanges across a transborder social field, composed by communities in Cuba, Florida and South America, interact with the limited liberalization carried out by the Cuban government in recent years. Who can take advantage of each type of opportunity and how they do so become political matters — that I want to explore too. More generally, I would like to contribute to the anthropological perspective on value and exchange, and to the comparative study of post-socialist reforms.

Q: How has becoming a PhD student affected your life?

I guess it arrived at the right time for me. Even though I had an academic job in my country, I was feeling that it was time for a change: time to go after other interests, and to have the great experience of living here in Canada, writing about new topics that I was not able to before. It is like a new life, a second chance.

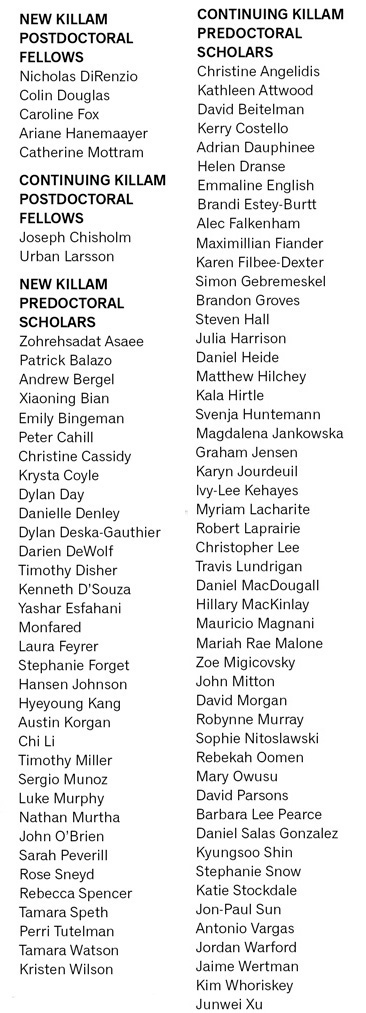

Killam Scholars at »ĆÉ«Ö±˛Ą

Since 1967, the Killam Bequest has provided more than $60 million to »ĆÉ«Ö±˛Ą including the Izaak Walton Killam Memorial Scholarships for master's and PhD students, and postdoctoral fellows. This scholarship allows its recipients to conduct outstanding research and make significant contributions to their intellectual communities.

The Killam Scholarship recognizes the very best in graduate and postgraduate education. »ĆÉ«Ö±˛Ą is one of only four universities in Canada to award Killam Scholarships and Prizes, which have made a huge difference in the lives and research of its recipient graduate students and postdoctoral fellows.

Here's a listing of this year's Killam Scholars: